| BANYAN BLOG |

banyan blog

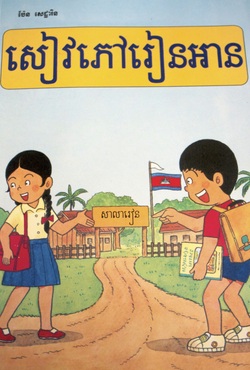

My Khmer lesson book My Khmer lesson book I have a confession. I have a hard time speaking my native language, Khmer. I can speak it but my proficiency is not where I would like it to be. I sometimes struggle to have in depth conversations with my Khmer friends and family members in Cambodia. I cannot read or write it and don’t understand Khmer humor which involves a lot of parables and proverbs. This language barrier has made me feel more like an outsider than I expected. I have lived here for almost a year and sometimes I feel more like a tourist rather than a Khmer born citizen. Most Khmers will speak to me in English first, then be surprised when I respond back in my choppy Khmer with an American accent. I tell them I am Khmer, born in Battambang. Then they look confused and ask, “Why don’t you speak better Khmer?” To which I say, “I’ve lived in the U.S. since I was five years old.” People may wonder why my parents didn’t teach me how to speak Khmer properly in the U.S., especially because my father was a Khmer-French literature professor. The fact is, it’s not my parents’ fault. It is my fault. It’s a story that may be familiar to many Khmers in the diaspora. The Early Years: Learning Speech and Communication During the Khmer Rouge

Experts say that the first few years of life are crucial for language development. Children learn from listening and watching people around them, especially the way parents speak to their children. I was born a few months after the Khmer Rouge regime in 1975. How Cambodians communicated with each other during the Khmer Rouge was very different than before the regime. To survive during that time you had to speak like an uneducated person, careful to not use language that would indicate social status or hierarchy. However this was rather difficult for the urban and educated class as the Khmer language is inherently a hierarchical language. The words you used to communicate with someone would indicate your social status, level of education or whether you were from the urban or rural area. For example, there are a few variations for the word mother or father, depending on whether one lived in the urban or rural area or were educated or non-educated. Before the Khmer Rouge the typical urban and educated family would usually call their mother “Mak” and father “Pa”. The typical rural and uneducated families would usually call their mother “Mai” and father “Pok” or “Uev”. Before the Khmer Rouge, my siblings called my mother “Mak”. During the Khmer Rouge, my mother told her children to call her “Mai.” She was scared we would become a target because that word was indicative of our former urban life and social status. The use of honorific titles also changed during the regime. In Khmer language it is customary to preface someone’s name with an honorific title when communicating with someone. These titles such as: Lok (generally for an older male with high social status); Bong (male or female who is older or around the same age); Ming (woman who is older than you but younger than your parents) or Om (male or female person older than you and your parents) are a sign of respect. When the Khmer Rouge took over most of these titles were abolished, especially the ones that indicated high social status and significant respect like “Lok.” These titles were now prefaced with the word “Mitt” (friend or comrade) before a person’s name. The respect and honor in which Khmer society bestowed upon elders and once high-ranking officials through language was diminished. Khmers may also use words from other languages such as French, Chinese, English and Pali. French was used mostly among the educated urban class since Cambodia was a French colony. As many Khmers are of Chinese origin, including my family, some Chinese words were interspersed into Khmer vernacular, especially words referring to family members. English words came later as the American presence in Cambodia increased during the Vietnam War. Since Cambodia is a Buddhist country, the religious community of monks, archar, nuns, and some highly educated people knew Pali. Monks and archars would chant Pali during religious ceremonies such as weddings or bonns (commemorating ancestors) and people would chant along. Demonstrating knowledge of French, Chinese, or English was dangerous to use for it indicated foreign influence of a former society that the Khmer Rouge were trying to destroy. The Khmer Rouge abolished religion therefore the use of Pali became obsolete. My father was fluent in French and Pali and my mom was of Chinese origin. They hid their knowledge of these foreign words. Before the war they would have been proud to speak them. My parents, like other urban educated Khmers were much more careful of the words they used during the regime. While I don’t remember much, I can imagine that I learned to speak Khmer in a very harsh way in those early years—more so than my siblings who were raised in Phnom Penh before the war. I never learned the Cambodian alphabet in a formal setting as my siblings did in school. At that time, I didn’t learn the importance of titles to show respect to others. I wasn’t chastised when I didn’t call someone Lok, Ming or Om as I would have been in a pre Khmer Rouge era. I was not exposed to any religious ceremonies in the camps. I picked up the rudimentary way in which people spoke and it has had an impact on the way I was first exposed to the language. Growing Up in the United States We finally immigrated to the United States in 1981 and my parents felt more comfortable speaking Khmer as they did before the war without the fear of constant persecution. In the U.S. we were once again taught the importance of honorific titles to show respect to other Cambodians. However, there were no formal means to learn the language in our Khmer community. The community where we lived in the VA/DC/MD metro area was dispersed and not as large or conglomerated as Long Beach or Lowell, Massachusetts. When we first settled in the U.S. we lived in a low income area in South Arlington where there was a large immigrant community (Asian/mostly Vietnamese and Latino). In the beginning the only person in my family that was fairly knowledgeable in English was my oldest brother, Sovanna, who had studied it for two years at Beng Trabek High School before the war. My parents had limited knowledge of it and my other siblings and I had to start from scratch. As such we were all more comfortable speaking Khmer around the house. Over time that gradually changed. We eventually settled in the suburbs of North Arlington where a vast majority of the population were middle class Caucasians. We were still very much fresh immigrants. Up until around age ten I was still fully conversant in Khmer partly from speaking it at home, watching Chinese movies dubbed in Khmer, and going to many Khmer gatherings with my parents. As a small community in the area Khmers needed each other for economic, social and emotional support to navigate a new way of life in America. We got together often for weddings, birthdays, graduations, bonns, or to visit each other’s homes for lunch or dinner or just to play cards. In the beginning I would speak Khmer with my other Khmer friends whom we would see often at these events. As the years went by, the children grew to adolescents and wanted to be more independent. I went to less and less functions. My Khmer friends and I grew apart, and when we did see each other occasionally, we stopped speaking Khmer to each other and spoke only English. My parents continued to speak Khmer to us at home but as hard as they tried it was difficult to instill the language and customs of their country. We were immersed by American culture. The functionality of speaking Khmer became less useful in our everyday lives. While my siblings spent a majority of their youth in Cambodia, they were much more exposed to the routine of Cambodian life and culture. Part of that still remained with them. Early on I was exposed to the routine of American life and culture which in many ways contradicted Khmer values. Khmer culture valued unquestionable obedience to parents and elders, the needs of the community/group over the individual (especially in the case of family), upholding a family's reputation was sacred, and the traditional role of girls. American culture valued independent thinking, freedom, individuality, and gender equality. I wanted to be the typical American teenager that had freedom and treated girls as equally as boys. I didn't understand the importance of upholding a family's reputation. I grew up in the suburbs of Arlington, VA, surrounded by American teenagers who went on dates, football games, played sports and joined clubs after school. I wanted do all these things but I was not allowed to because I had to be a “good” Cambodian girl. I was frustrated and didn’t understand these cultural values. The identity and the language became more of a burden than a blessing. My parents didn’t understand the American culture of allowing such freedom to teenagers. Not speaking Khmer, rejecting Khmer culture and customs and showing no interest in learning them was my way of rebelling against my Khmer identity. Full Circle: Learning Khmer Again In 2004 I went to Cambodia with my parents. Time and maturity had changed my outlook on my culture as I no longer felt the pressure of "fitting in". I understood that having this heritage and knowing the language made my life richer. I was ready to go back. It had been over 20+ years since I stepped foot in the country. That trip was the turning point in my life when I discovered I was ready to embrace my Khmer identity, something I buried for so long. Once in Cambodia I was immersed in Khmer culture and language. For the first time ever, I felt a deep connection to my heritage. While I was there I realized my Khmer was rusty and I had the vocabulary of a ten year old. It was challenging to constantly communicate in my native tongue. I was embarrassed and realized how little I knew about my culture, my language and regretted turning my back on it for so long. But I made a vow to come back and learn. Ten years later I am back in Cambodia. I am trying to keep that vow. Over the last three months I have been working with a Khmer teacher to learn how to read and write Khmer and improve my vocabulary. I thought it was going to be easy since I spoke Khmer. It has been harder than I thought, especially learning how to read and write. I am fortunate that I have a solid foundation to start from, although that foundation started on shaky grounds. It began with the harsh living conditions, and rudimentary words and phrases in which the Khmer language was transmitted to me during the Khmer Rouge. Learning was not a priority, survival was. Then in the U.S. the Khmer language, culture and customs were difficult to maintain, especially for the younger generation who was searching for a sense of belonging in a new world. Our outside life was easier when we adapted but our home life struggled to compete. My family, like many Khmer diaspora, were uprooted from our homeland and needed to plant new roots and adapt to our new environment. For the older generation, those roots were already entrenched in their homeland, they never fully adapted. They already knew who they were and where they belonged. For the younger generation those roots thrived in a new environment and blossomed but yet many of us still felt out of place and incomplete. Our sense of belonging was shallow even if we didn't realize it in our youth. I am hoping that by relearning Khmer in the proper way it will help me to understand the context of Cambodian history, fully absorb the richness of it’s culture, connect with other Khmers in a more meaningful way, and most of all, have a deeper understanding of what it means to be Khmer.

11 Comments

Marie

5/25/2014 11:05:12 pm

I thourghly enjoyed reading your blog and can see my family in your blog easily.I look forward to reading future blogs from you,good luck with your studies.Best of wishes to you.

Reply

Mitty

5/26/2014 12:55:54 am

Thank you Marie for your nice comments and hope you will visit again soon!

Reply

1990sbaby

5/26/2014 12:27:38 am

I randomly came across your blog and I can honestly relate to this. You nailed it on the spot for me. I felt like I was the only one. Thanks for the inspiration!

Reply

Mitty

5/26/2014 12:58:13 am

Thank you 1990s baby. It's a story we all share but not enough with each other. You're not alone in feeling that sense of isolation.

Reply

Kenda

5/26/2014 12:33:17 am

Thank you for sharing!! I can relate to your experience as I started learning how to read and write khmer about four years ago.

Reply

Mitty

5/26/2014 01:03:57 am

Thank you Kenda. I can relate to your feelings of being torn. Truth is it's hard to choose, too much pressure, conflicting cultural values make it difficult. But over time I've realized we don't have to chose, we have the gift of being both, but we can only realize that once we embrace the journey.

Reply

Nalin

5/28/2014 08:50:48 am

Thanks for sharing. Just like the other readers, I can relate to your story. My dad can read/write in Khmer, but my mom is illiterate. I was fortunate to have grown up in a large Khmer community in Stockton, CA that offered Khmer reading & writing classes. I'm glad that you are re-learning Khmer. Best of luck to you!

Reply

Jeff

7/3/2014 06:58:30 am

Hi Nalin. Could you give me more information about the Khmer reading & writing classes in Stockton, CA. Thanks.

Reply

Mitty

5/28/2014 03:04:26 pm

Dear Nalin,

Reply

Rob T

6/28/2014 01:23:12 am

Hi Mitty,

Reply

Mitty

6/28/2014 12:57:08 pm

Dear Rob,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

FEATURED INMOST POPULARThe Journey Archives

October 2022

follow |

All Rights Reserved