| BANYAN BLOG |

flashbacks

"Remember the days of old; consider the generations long past. Ask your father

and he will tell you, your elders, and they will explain to you."

-Deuteronomy

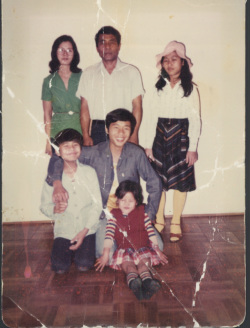

1981,VA: Refugees. First family photo.

1981,VA: Refugees. First family photo.

I have always been interested in knowing my parents story, how we managed to survive the Khmer Rouge, and our miraculous journey to the United States. In 2003 I started recording interviews with my parents to ask them questions about our past. With my father’s passing these interviews have become even more cherished memories.

Over a decade has passed since I’ve listened to these interviews, but they still seem like yesterday since we sat around the table talking about what life was like for them when they were growing up. Through these conversations I get a glimpse of Cambodia’s political history; from French rule, independence, civil war, to finally, the Khmer Rouge. In listening back, there are many gaps to these stories, which I am seeking to fill during my time in Cambodia.

I hope you will take a journey through time to get a glimpse of Cambodia’s past through my family's story.

exodus: april 17, 1975

The morning started off like any other day. Yey Om, my aunt, woke up at 5AM to make babor (rice porridge) for the family. The house was quiet with only the sound of the children’s breath rising and falling gently in their peaceful slumber. I admired their innocence and ability to forget that the world was falling apart around us.

Over the last few months, there was heavy bombing and rocket fire approaching closer and closer into the city center. I would wake up in the middle of the night to the thunderous sounds of rockets and gunfire in the distance, followed by a sense of panic, wondering when the next one would come. A few times we prepared our belongings together; gold, jewelry, money, anything of value, in case we had to leave the city, but we never had the courage to leave. We hoped for a miracle that one-day soon, the fighting would end, and we could go back to our normal life.

But life was all but normal. Schools were closed, which meant, my husband could no long work, and the children could no longer go to school. The hospital was still open but the day before, the government issued a 24-hour curfew. We were to stay home. I could hear the bombings were getting closer and closer and plumes of smoke in the distant sky choking a city under siege.

Read More...

Over the last few months, there was heavy bombing and rocket fire approaching closer and closer into the city center. I would wake up in the middle of the night to the thunderous sounds of rockets and gunfire in the distance, followed by a sense of panic, wondering when the next one would come. A few times we prepared our belongings together; gold, jewelry, money, anything of value, in case we had to leave the city, but we never had the courage to leave. We hoped for a miracle that one-day soon, the fighting would end, and we could go back to our normal life.

But life was all but normal. Schools were closed, which meant, my husband could no long work, and the children could no longer go to school. The hospital was still open but the day before, the government issued a 24-hour curfew. We were to stay home. I could hear the bombings were getting closer and closer and plumes of smoke in the distant sky choking a city under siege.

Read More...

back to battambang: part i & ii

PART I:

The sun was beating down on us that long February afternoon in 2004. Even though it was technically the “cool season” in Cambodia, being out in the open and dry fields for hours took a toll on our bodies. We were thirsty, hot, sweaty and disoriented. I wondered, what are we even doing here?

Then I looked around and realized the crossroads of fate was standing right in front of me. We were meant to be here. Destiny brought me back to Battambang, to Oak-a-bao, the Khmer Rouge camp I was born in over 20 years later. But seeing my birthplace was not the purpose of our visit. We were there to find the burial site of my family members who had died during the “bad times”. I will never forget my first visit back to Battambang, our visit back to Oak-a-bao. We were all looking for closure, all in our own way.

Read More...

PART II:

Over 20 years had passed since my father buried my brother, Sakeda, and my grandparents, Kong Sreng and Yey Eng in Battambang. Before the Khmer Rouge, family’s of the deceased conducted intricate funeral ceremonies for their loved ones in traditional Cambodian culture. However, the Khmer Rouge did not allow any mourning or attachments to family. Tradition and culture was destroyed and humanity along with it.

My father had to bury his son and parents-in-law without any Buddhist ceremonies, without any monks to help guide them into the next life. There was nothing he could do to commemorate their death or provide any offerings to them in the afterlife.

Instead, he had to bury his family unceremoniously and carry on as if nothing happened. My uncle, Pa Om, felt he never completed his duty as the filial son in his parents’ death. Even though decades had passed, finding these bones meant they could finally give the proper rituals for their loved ones. More so, they could find peace and closure through this process.

My father thought if he ever had the chance to go back to Oak-a-Bao, he was sure he could find the bones to give them a proper burial. For years, he also wanted to go back but was concerned about the safety. My uncle Om Ngat, who had lived in Battambang since 1979, was uncertain whether it was still safe to go. Pa Om was determined with or without anyone’s help. Finally they all decided they would take the chance and go together.

Read More...

The sun was beating down on us that long February afternoon in 2004. Even though it was technically the “cool season” in Cambodia, being out in the open and dry fields for hours took a toll on our bodies. We were thirsty, hot, sweaty and disoriented. I wondered, what are we even doing here?

Then I looked around and realized the crossroads of fate was standing right in front of me. We were meant to be here. Destiny brought me back to Battambang, to Oak-a-bao, the Khmer Rouge camp I was born in over 20 years later. But seeing my birthplace was not the purpose of our visit. We were there to find the burial site of my family members who had died during the “bad times”. I will never forget my first visit back to Battambang, our visit back to Oak-a-bao. We were all looking for closure, all in our own way.

Read More...

PART II:

Over 20 years had passed since my father buried my brother, Sakeda, and my grandparents, Kong Sreng and Yey Eng in Battambang. Before the Khmer Rouge, family’s of the deceased conducted intricate funeral ceremonies for their loved ones in traditional Cambodian culture. However, the Khmer Rouge did not allow any mourning or attachments to family. Tradition and culture was destroyed and humanity along with it.

My father had to bury his son and parents-in-law without any Buddhist ceremonies, without any monks to help guide them into the next life. There was nothing he could do to commemorate their death or provide any offerings to them in the afterlife.

Instead, he had to bury his family unceremoniously and carry on as if nothing happened. My uncle, Pa Om, felt he never completed his duty as the filial son in his parents’ death. Even though decades had passed, finding these bones meant they could finally give the proper rituals for their loved ones. More so, they could find peace and closure through this process.

My father thought if he ever had the chance to go back to Oak-a-Bao, he was sure he could find the bones to give them a proper burial. For years, he also wanted to go back but was concerned about the safety. My uncle Om Ngat, who had lived in Battambang since 1979, was uncertain whether it was still safe to go. Pa Om was determined with or without anyone’s help. Finally they all decided they would take the chance and go together.

Read More...

A different khmer rouge leader

Today, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), otherwise known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal (KRT) presented the verdict to two of the highest-ranking surviving Khmer Rouge leaders. Noun Chea, also known as Brother Number 2, and Khieu Samphan, the Head of State for Democratic Kampuchea, were found guilty by the international tribunal for crimes against humanity. They both received a life sentence.

Under their leadership, they were responsible for the deaths of over 1.7 million people who died at their hands by starvation, execution and rampant disease. Hearing this verdict and their crimes is painful for many who wanted see something more.

The judgement today stripped the victims, living and dead, the right to see these leaders suffer as they did. Yet despite the angry emotions I felt today, I also remembered a different kind of Khmer Rouge leader, one who risked his life to save our family.

Read More...

Under their leadership, they were responsible for the deaths of over 1.7 million people who died at their hands by starvation, execution and rampant disease. Hearing this verdict and their crimes is painful for many who wanted see something more.

The judgement today stripped the victims, living and dead, the right to see these leaders suffer as they did. Yet despite the angry emotions I felt today, I also remembered a different kind of Khmer Rouge leader, one who risked his life to save our family.

Read More...

three memories of the coup

March 18, 2014 marked 44 years since the coup by General Lon Nol to overthrow Prince Norodom Sihanouk from power. These three stories tell firsthand accounts by three people who recalls what happened that day, and chain of events that occurred thereafter. The first is written by Mr. Chhang Song who was working on Prince Sihanouk's information team as an editorial assistant at the time of the coup. He later became Minister of Information in the Lon Nol government. The second story is from my mother who lived in Phnom Penh at the time and recalled the new government telling the people to "stay quiet and still" on that day. The third story is from my aunt who lived in Takeo Province and recalls a violent uprising by the people against the coup. Read these three stories to get a first hand account of what happened in Cambodia before and after the coup.

"THE OVERTHROW": BY CHHANG SONG-03/20/2014

"STAY QUIET AND STILL": BY YOU SAKHAN-03/23/2014

"THE UPRISING": BY AUNT (OM) EAR-03/26/2014

"THE OVERTHROW": BY CHHANG SONG-03/20/2014

"STAY QUIET AND STILL": BY YOU SAKHAN-03/23/2014

"THE UPRISING": BY AUNT (OM) EAR-03/26/2014

Remembering A Nightmare

Today, January 7th, 2014, marks 35 years since Cambodia became free from the Khmer Rouge nightmare. This day commemorates when Vietnamese troops seized Phnom Penh from the Khmer Rouge. For three years, eight months and twenty days, millions of Cambodians suffered by starvation, disease, and lived under the constant threat of execution. It is estimated that nearly 2 million Cambodians perished under the bloody regime. For Cambodians, it is a day to reflect on where the country was over 35 years ago and for the survivors to remember the nightmare they lived.

When the Vietnamese took over the capital that day, most Cambodians, like my family, were not there to see it. Instead, we were hiding deep in the woods of Battambang in northwestern Cambodia. We were struggling to survive, unaware that freedom was near. I interviewed my mother and asked her to tell me how the nightmare started and how it finally ended. This is what she recalls...

Read More...

When the Vietnamese took over the capital that day, most Cambodians, like my family, were not there to see it. Instead, we were hiding deep in the woods of Battambang in northwestern Cambodia. We were struggling to survive, unaware that freedom was near. I interviewed my mother and asked her to tell me how the nightmare started and how it finally ended. This is what she recalls...

Read More...

hot pot holidays

One of my favorite songs is James Taylor’s “Carolina on My Mind”. Though I’m not from Carolina, the song reflects a universal feeling of being homesick, when one is far away from the place where fond memories were made, where you were among people who shaped you, and where everything seemed familiar.

While I love being in Cambodia, there is a part of me that is feeling a bit homesick. This feeling seems to grow stronger as the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays are approaching. Growing up in the U.S. we never really celebrated these holidays in the traditional American way. We didn’t have turkey, ham or mashed potatoes but Yao Hon or Cambodian Hot Pot, a meal composed of a savory broth, assortment of meat and vegetables and nom banh chok (thin rice noodles).

Read More...

While I love being in Cambodia, there is a part of me that is feeling a bit homesick. This feeling seems to grow stronger as the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays are approaching. Growing up in the U.S. we never really celebrated these holidays in the traditional American way. We didn’t have turkey, ham or mashed potatoes but Yao Hon or Cambodian Hot Pot, a meal composed of a savory broth, assortment of meat and vegetables and nom banh chok (thin rice noodles).

Read More...

the first memories

Yesterday marked the 60th year when Cambodia reclaimed her sovereignty from French rule. Yet, the road to independence was not always easy and the years that followed would lead to decades of political instability.

My mother, Sakhan, was born in Takeo Province, Bati District in 1940. She has witnessed many of Cambodia’s historical transitions, from living under French rule, independence, civil war, to finally the horrors of the Khmer Rouge. Now she is back in Cambodia witnessing a new phase of the country’s political development. While she loves her country, and her heart belongs here, there will always be a part of her that fears Cambodia’s peace and stability could fall apart at any moment. This fear started at a young age when her first childhood memories were of grenade attacks and arrests.

Read More...

My mother, Sakhan, was born in Takeo Province, Bati District in 1940. She has witnessed many of Cambodia’s historical transitions, from living under French rule, independence, civil war, to finally the horrors of the Khmer Rouge. Now she is back in Cambodia witnessing a new phase of the country’s political development. While she loves her country, and her heart belongs here, there will always be a part of her that fears Cambodia’s peace and stability could fall apart at any moment. This fear started at a young age when her first childhood memories were of grenade attacks and arrests.

Read More...

the power of education

My father was born in Takeo Province, Cambodia in 1940. I knew growing up that this was not his real birthdate. My understanding was that he changed his birthdate at the Thai Refugee Camp to be younger so that he could prolong his retirement in the U.S. It wasn’t until I started my first interview with him in 2003 that I found out he changed his age much earlier in life and for a more important reason.

Read More...

Read More...

© banyan blog 2013-2022

All Rights Reserved

All Rights Reserved