| BANYAN BLOG |

banyan blog

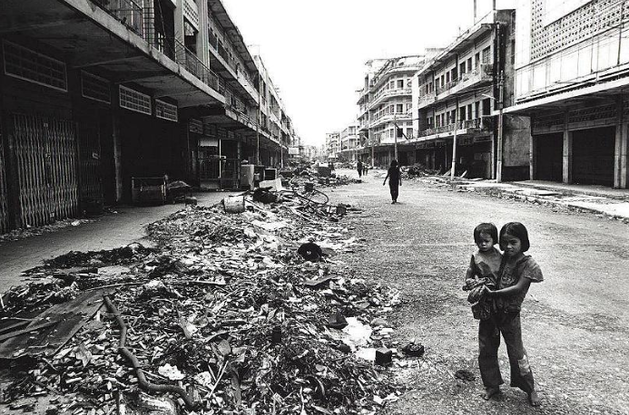

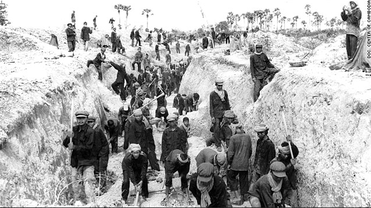

Those who don't know history are doomed to repeat it", Edmund Burke, Statesman Today, January 7th, 2014, marks 35 years since Cambodia became free from the Khmer Rouge nightmare. This day commemorates when Vietnamese troops seized Phnom Penh from the Khmer Rouge. For three years, eight months and twenty days, millions of Cambodians suffered by starvation, disease, and lived under the constant threat of execution. It is estimated that nearly 2 million Cambodians perished under the bloody regime. For Cambodians, it is a day to reflect on where the country was over 35 years ago and for the survivors to remember the nightmare they lived. When the Vietnamese took over the capital that day, most Cambodians, like my family, were not there to see it. Instead, we were hiding deep in the woods of Battambang in northwestern Cambodia. We were struggling to survive, unaware that freedom was near. I interviewed my mother and asked her to tell me how the nightmare started and how it finally ended. This is what she recalls...  KR soldiers entering Phnom Penh, April 1975. Photo Credit: DC-CAM KR soldiers entering Phnom Penh, April 1975. Photo Credit: DC-CAM PART I: BEGINNING OF A NIGHTMARE On April 17th, 1975, the Khmer Rouge, dressed in black pajamas and red checkered scarves, paraded triumphantly into Phnom Penh. They were greeted by jubilant crowds of people waving white flags and shouting JAY-YO! JAY-YO! (victory). People were happy the Khmer Rouge took over from the Lon Nol government and thought the long and brutal civil war was finally coming to an end. For a brief moment, there was hope for peace. It was also your sister’s 10th birthday that day.  Lon Nol soldiers surrendering weapons. Photo credit: DC-CAM Lon Nol soldiers surrendering weapons. Photo credit: DC-CAM After the parade, the Lon Nol soldiers had laid down their weapons in piles in the middle of the street as commanded by the Khmer Rouge. They thought they were peacefully surrendering. Only a few hours passed when the expectations of peace and happiness quickly turned into violence and terror. The Khmer Rouge ordered the entire population of Phnom Penh; men, women, children, the sick and elderly to evacuate because the Americans were going to bomb the city. We were told to only take a few days worth of food because we would come back soon. I packed some clothes for the children, food, photographs, medicine, jewelry and some money, not knowing how long we would be gone. Your father took his diplomas.  Massive evacuation of Phnom Penh. Photo credit: DC-CAM Massive evacuation of Phnom Penh. Photo credit: DC-CAM The Khmer Rouge didn’t tell us to go to any specific place, only that we had to get out of the city. We followed the crowds of people moving out of Phnom Penh and walked towards Takeo, our home province. The scene was surreal, hundreds of thousands of people walking in the streets, carrying their children, pots and pans, rice, suitcases and few belongings to survive. On the way, the Khmer Rouge had checkpoints and would stop people and ask them what they did for a living. A Khmer Rouge soldier asked your aunt’s cousin what he did. He was honest and told them he was a soldier. They took him away to the woods then we heard gunshots. We then realized the Khmer Rouge wanted to kill anyone who was highly educated, associated with the previous government or any sign of wealth. We quickly learned to hide our identities as more gunshots could be heard in the distance as former police, soldiers, and others who worked for the government were taken away for questioning. Out of fear, I threw away the photographs. They were pictures of all my children, our wedding, our house, when I was a nurse, your father teaching, my parents, and many other precious memories. Our entire life was thrown in the river. Your father threw away his diplomas in the river, his most prized possessions. We walked over 70 kilometers from Phnom Penh to Takeo and settled into our new life. I had no idea I was pregnant with you until two months after we left the city when I started getting nauseous. We were only in Takeo for six months when your father asked the commune leader to move to Battambang province. He knew that Battambang was abundant with the Pursat oranges and thought we would have a better chance of survival. We also wanted to be with my family who was already there. The request was granted and a truck picked us up from Takeo to take us to Battambang. We were squeezed on the back of a truck like sardines. I was seven months pregnant with you at the time and rode the entire seven hour bumpy journey standing up.  Another picture of a Khmer Rouge labor camp. Photo Credit: DC-CAM Another picture of a Khmer Rouge labor camp. Photo Credit: DC-CAM Life in Battambang was worse. You were born in December 1975 in a hut your father made with no medicine and very little food. Starvation and executions were just as rampant and our family was not spared by either of the two. Your brother died of starvation in 1976, soon after we had moved to Battambang. He was only 11 years old. Another of your brothers was executed in February 1979. I was sick and dying of starvation and he had stolen some rice for me. A Khmer Rouge soldier caught him and accused him of stealing rice to give to the Vietnamese and took him away. We never saw him again. We were never allowed to grieve because they would have killed the entire family. This was one month after the “liberation” of Phnom Penh. We were so close to escaping. He was only 16 at the time. PART II: END OF A NIGHTMARE Vietnamese forces entering Phnom Penh, Jan 7, 1979. Photo credit: DC-CAM Vietnamese forces entering Phnom Penh, Jan 7, 1979. Photo credit: DC-CAM On January 7th, 1979, we were living deep in the woods of Battambang in Oak-a-Bao, not knowing that the Vietnamese had taken over Phnom Penh. But throughout the commune, whispers and gossip was circulating that the Vietnamese were near. We thought there might be hope to finally escape. We knew things were changing. The Khmer Rouge soldiers were starting to evacuate the commune and take the villagers to the mountain. This time, they said the Vietnamese were coming and we had to escape. We were one of the last families to leave the commune. From Oak-a-Bao, the Khmer Rouge soldiers ordered us to walk to Phnom Tra Chakt Chut, a nearby mountain. We had no choice but to follow. On the way your father fell sick from drinking bad palm wine a few days beforehand. He was so thirsty that he would sneak out to make this at night. After drinking this bad batch, he could not walk and told me to go on without him and to save myself and the children. I refused and said “if we die, we die all together”. At night I made porridge from what little rice I was given and smothered it all over his back and stomach. Miraculously, the next day he felt better. We continued on our long march to the mountain. On the journey, I would see dead bodies in shallow trenches. These bodies had been killed by a gunshot wound or a knife. Men, women and children were killed indiscriminately by the Khmer Rouge. Who knows what their crimes were. It was the most horrific site I had ever seen in my entire life and is forever etched to my memory. Once at Phnom Tra-chak Chut the Khmer Rouge soldiers were still making the people work. Instead of digging canals or planting rice, they were commanding us to hide the rice from the Vietnamese. One late evening a Khmer Rouge soldier summoned your father. When they called you late at night, it was usually to execute you. I didn’t think I would ever see him again. An hour later he came back telling me that they ordered him to work. We stayed at Phnom Tra-Chakt Chut for almost two weeks. With every day, Khmer Rouge soldiers were disappearing either deeper into the woods or going to fight the Vietnamese. Every day less and less soldiers were at the camp and one day they were just all gone. We had heard the Khmer Rouge soldiers were hiding, waiting to see if anyone would escape, and when they did, they would shoot them. One day, Bou Chuom, a distant uncle heard that the Vietnamese soldiers were close. He said it was a good opportunity to escape. We finally mustered the courage to leave. Even if the soldiers were hiding throughout the mountain, waiting to shoot us, it was better than waiting to die there. We took our chances and left. We started walking down the mountains and we were met by other groups of people. Day in and day out more and more people showed up. With every step we took, we were afraid that either the landmines would get us, or a Khmer Rouge soldier would shoot us from behind a tree. We grew in numbers and walked together by day and rested at night. We finally reached the bottom of the mountain and I began to feel a sense of hope that we might survive. That hope grew stronger when I heard a song on the radio, the Rorm Vong (Phak Tabat Prey), a song commonly played around Khmer New Year before the Khmer Rouge. During the regime they never played this type of music, it was forbidden, only revolutionary music. When I heard that song, I knew a part of our normal life was coming back. I knew we were finally free from the Khmer Rouge and we could finally escape this nightmare.

11 Comments

Chisako

1/7/2014 12:19:56 am

I'm so glad your mother was able to share your family's story. That in itself is an act of courage.

Reply

Mitty

1/7/2014 10:18:34 am

Thank you Chisako. She is a brave woman and a survivor.

Reply

B

1/7/2014 01:36:32 am

Very moving and scary first hand account.

Reply

Mitty

1/7/2014 10:19:39 am

Thank you B for taking the time to read it.

Reply

Dear Mitty,

Reply

Mitty

1/7/2014 10:30:28 am

Dear Sonny,

Reply

Qiao Xue

1/7/2014 01:29:21 pm

"Your father threw away his diplomas in the river, his most prized possessions." What a horrible, beautifully-told remembrance of this atrocity. Thank you to you and your mother for re-hashing what was undoubtedly a terrifying period in your lives. If only the lessons of this social experiment could extend to 2013 and beyond....the world doesn't need another Choeung Ek or Year Zero.

Reply

Mitty

1/7/2014 01:55:03 pm

Dear Qiao Xue: I always knew education was important to my father but have only recently understood how much it meant to him. He worked so hard to get these diplomas and I now realize how hard it must have been throw them away, and never to return to that life again. We must do what ever it takes to never return to this. Too many lives lost and forever changed for nothing.

Reply

Mitty

1/7/2014 01:56:11 pm

By the way, thank you for your comments and taking the time to read it.

Trudi Woods

1/10/2014 03:40:04 am

I thank you for sharing your mothers story...I have visited many of the places you tell about, Battenbong esp. sticks in my mind, the night market, the country side and the circus children...a tuku driver told us a story very similar to your mothers experience. I hope peace comes again to Cambodia and the goodness of her people rise above the evil now resurfacing

Reply

Mitty

1/11/2014 10:52:39 pm

Dear Trudi,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

FEATURED INMOST POPULARThe Journey Archives

October 2022

follow |

All Rights Reserved